INTERVIEW BY KATHERINE MEZZACAPPA

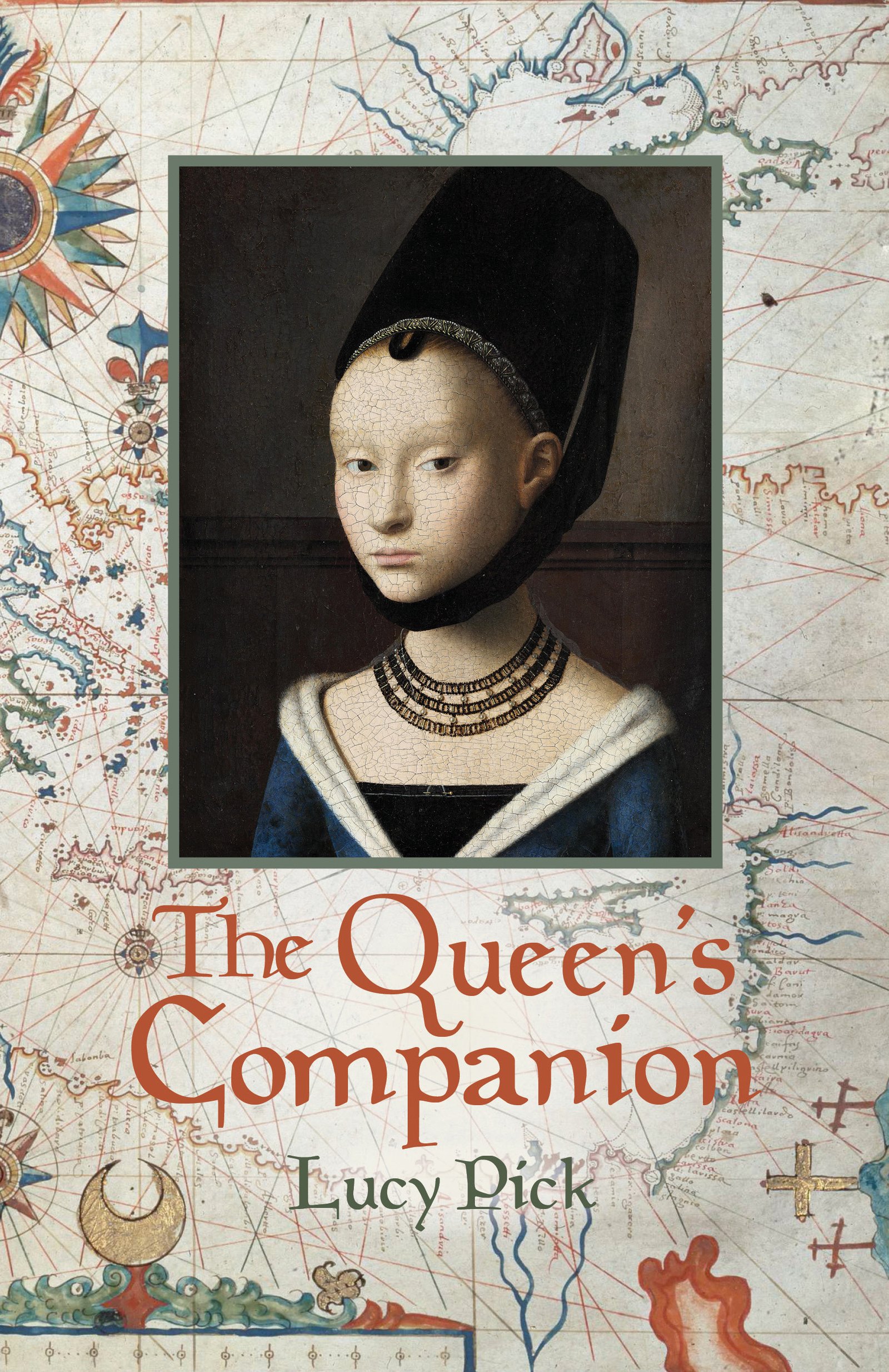

Lucy Pick is a historian of the thought and culture of medieval Spain who has published on Christian, Muslim, and Jewish relations and the intersection of gender, religion, and royal power. She taught for over twenty years at the Divinity School of the University of Chicago. Her first historical novel, Pilgrimage (Cuidono Press, 2014) explored betrayal, friendship, miracles, healing, and redemption on the road to Compostela. In her latest novel, The Queen’s Companion, a minor character from Pilgrimage takes center stage.

How would you describe The Queen’s Companion and its themes in a couple of sentences?

When Lady Aude encounters Eleanor of Aquitaine on her way to the Holy Land, the two women’s stories weave through the crusades and civil strife of Flanders. The Queen’s Companion tells a story of women’s friendships and the meaning of home against a backdrop of war and intrigue.

Your new novel was preceded by Pilgrimage, ten years ago, and one of the supporting characters in The Queen’s Companion takes center stage. Had you always intended to write a follow-up?

Your new novel was preceded by Pilgrimage, ten years ago, and one of the supporting characters in The Queen’s Companion takes center stage. Had you always intended to write a follow-up?

I didn’t plan a follow-up, but one character stuck in my head: Aude, the young step-mother of Pilgrimage’s main character, Gebirga, whose arrival at the family home is the cue for Gebirga to leave. Aude is horrible in her few scenes, and she is pregnant. What made her so horrible, I wondered, and what happened to her afterwards? So I wrote a story that could be read independently of Pilgrimage to answer those questions.

You have built a successful career as an academic historian, so it’s no surprise that you are an expert in the research involved in historical fiction. What have been the challenges in crossing over to fiction?

The biggest challenge is not telling every single historical fact you know about the period! Also challenging is becoming attuned to the material culture of everyday life – what people ate and wore and slept on to create characters who moved through real, physical space, touching and seeing and using things. Physical objects are tools that help our imaginations project backwards into times and places that are completely unfamiliar to us. I want readers to stand beside my heroine, feeling the scratchy wool or cool silk on her back, handling the bone spoon or silver cup she uses.

Writing fiction as an academic historian allows me to write about people who get less attention from history, and to endow them with personalities and feelings. I can write in a speculative way about events that I can’t write about as a historian. For example, my plot here develops out of a lost year in Eleanor’s life between her arrival in Antioch in 1148, when she meets Aude, and her departure from Acre with the king in 1149. That’s grist for fiction.

Tell me how you arrived at your heroine, Aude. I was intrigued that with Aude, your story subverts the common pattern in historical fiction of a mature noble mistress and a young attendant.

I wanted to write about two women who were friends, and whose friendship grew and deepened over the course of the book, so it was helpful to have Eleanor, the queen, be young and Aude, the attendant, be older, her experience and worldliness balancing Eleanor’s superior rank. Eleanor was not in the novel at all when I began writing! I wanted to write in the first person, and I wanted Aude to tell her story. Medieval women – medieval people in general – did not write long personal letters or narrative histories. I needed an audience so I created a kind of Canterbury Tales out of Eleanor and her attendants, where the destination was Jerusalem, then Eleanor’s story grew to match Aude’s.

Aude herself grew from fragments. The Aude of Pilgrimage was young, sad, a bit self-centered, and no shrinking violet. Her mother’s name and demeanour was inspired by an icon of Saint Theodosia from Mount Sinai. After I put those two very different temperaments together, it all flowed naturally.

The queen of your title is Eleanor of Aquitaine who has had a mixed reception in popular historical fiction – which has often paid attention to her second marriage rather than the one described here. Can you say something about how you developed the fictional character of someone who others (along with the historical record) have said quite a lot about?

There’s less fiction about the early Eleanor, and fewer historical sources, but those we have are evocative, like the tale of Eleanor and her women dressing like Amazons when the French took the crusader cross at Vezelay, which I retell in my first chapter.

Eleanor’s character changed and deepened as I revised the novel. I use the rumours she had a relationship with her uncle in Antioch and in early versions, this was a salacious story of incest. My understanding of their relationship, and my telling of it, changed sharply after the #MeToo movement. She was young, about twenty-three, and he was much older. My Eleanor is a vulnerable woman whose exuberant heart leads her to be taken advantage of, but as she comes to terms with her situation, I think you can see hints of how, perhaps embittered by what she endures, she becomes the more familiar Eleanor we know from fiction and history. We meet that Eleanor briefly at the very end of the novel.

It’s evident that you understand your locations: Vézelay, Bruges and so forth. How did you manage to strip back the current appearance of locations to their twelfth-century appearance?

It’s evident that you understand your locations: Vézelay, Bruges and so forth. How did you manage to strip back the current appearance of locations to their twelfth-century appearance?

Vezelay is still a small town, and you can still see the field where the crusader host met. Bruges has changed out of recognition, but my historical source, Galbert of Bruges’s The Murder of Charles the Good helped there. Likewise, the chronicle recounting its conquest from the Muslims helped there. Al-Lawza is a real crusader villa with details that come from an archaeological report.

Is The Queen’s Companion a feminist novel, and what messages do you think Aude’s story might bring to our understanding of the choices contemporary women are permitted?

It is a feminist novel in the sense that the concerns of the women who are its subject are at its heart, and are not always the doings of, or their feelings for, men. And Eleanor of Aquitaine was not alone as a woman who wielded both power and wealth in her period. I think a lot of the questions we all face as humans living in bodies that will die have resonance across the centuries, and I tackle some issues here, like abortion and sexuality, that will feel very familiar.

What was the last great book you read?

Fiona Carr, The Tower.

HNS Sponsored Author Interviews are paid for by authors or their publishers. Interviews are commissioned by HNS.

![]()